The art of opal cutting

featured newsAustralia’s national gemstone is also one of the most complicated to cut. GAA opal experts Anthony Smallwood and John Krook explain why it is an art form in its own right.

The cutting and fashioning of gemstones is an art. It is often forgotten that while there is an inherent beauty in the crystal nature of transparent gemstones, this is not always present in the opaque or translucent gemstones.

Non-transparent stones – even those of great beauty or value such as opal – are often mistakenly referred to as ornamental or semiprecious gems.

Opal is such a mysterious gemstone that often its beautiful play of colour is hidden. Only an experienced opal cutter can produce an exquisite gemstone.

So the opal cutter is an artisan of great importance, who alone can reveal an opal’s hidden beauty.

So how does an opal cutter begin? An examination of the rough is key, as the origin and variety of opal will often determine what a cutter does; in this way opal is like no other gemstone.

A cutter working on a Lightning Ridge (NSW) black opal will require a different skill to a cutter who is about to produce a gem from Queensland boulder opal, who again will treat the rough material differently to the cutter of a superb South Australian Andamooka or Coober Pedy crystal opal. Each variety possesses its own unique challenge for the cutter in terms of the thickness of the opal and the material that forms the back of the gem (ironstone for boulder, black potch for black opal, and so on).

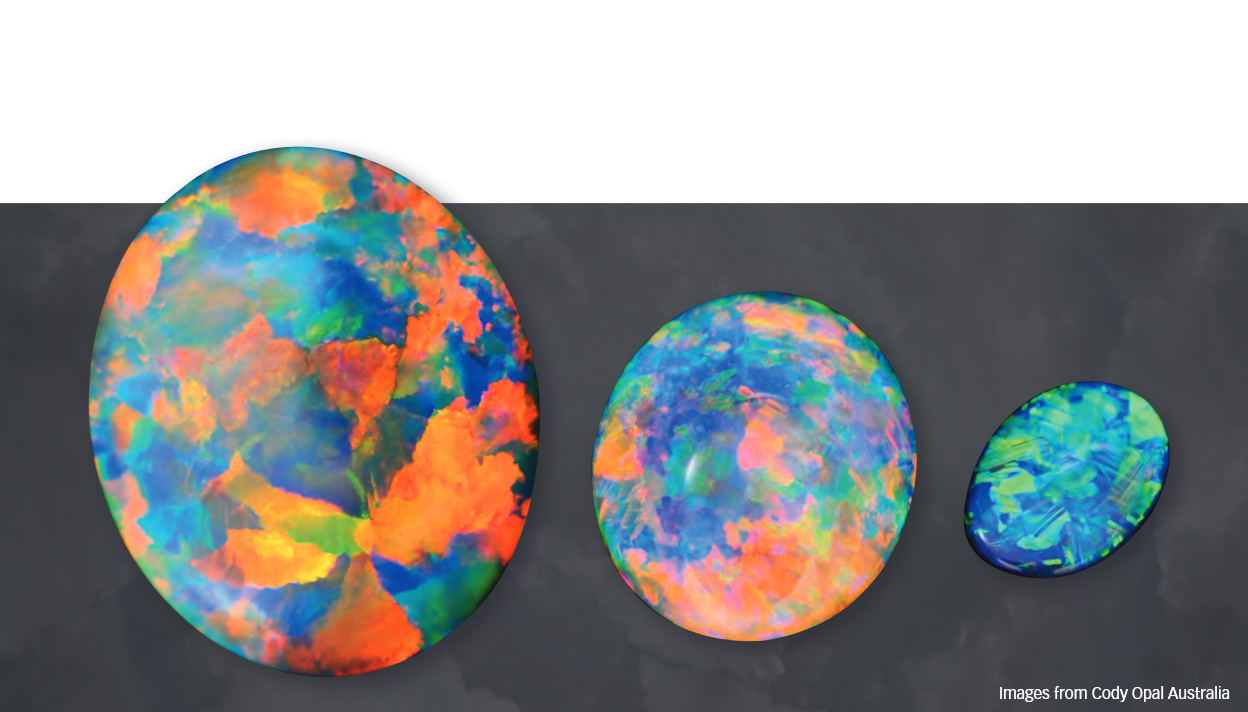

Once the opal cutter has established the thickness of their opal they can assess what shape will produce the best gem from the rough and show the best “face”.

Generally, the cutter’s biggest focus is to create a full-faced gemstone of the most vibrant colour and to polish it to a mirror finish. Every opal is unique, so a cutter’s experience and intuition are important to success.

When it comes to boulder opal, the cutter must first assess how thin the opal veneer on the ironstone might be.

There’s often not much to work with here. Often less than a millimetre in thickness, the cutter won’t want to waste any precious opal. So they will interracially expose the layer of colour and follow it or trace it in an undulating nature to expose the vibrant colours. To allow this, boulder opal gems will often have an irregular surface and be cut in a free shape or free-form with irregular outline.

The opal cutter working with Lightning Ridge black opal, however, will often have the benefit of a thicker colour bar (as compared with boulder opal), so may choose to create a cabochon; cutting a high-domed precious gem if the colour bar agrees, or a lower-domed cabochon if that’s all that is available.

It is likely he will produce an oval-cut gemstone as this is generally the most commercially viable shape. But free-form and irregular shapes are also produced for exotic designer jewellery.

Crystal opal and Light opal may be used to create both standardised sized opal cabochons for jewellery and for more individually shaped free-form and opal carving. Much of the commercial grade opal jewellery with standardised, calibrated sizes is cut from Light and Crystal opal from the South Australian fields.

That’s not to say plenty of these stones aren’t still available for more exquisite shapes and carvings.

In considering the ‘face’ of the opal the cutter also takes into consideration the possibility of finding one of many named opal patterns – including ‘butterfly wing’, ‘Chinese writing’, ‘harlequin’ (often misused), ‘rolling flash’ and ‘flagstone’ among others.

Opal folklore is as vibrant as the stone; unique to Australia and to the outback regions of Australian pioneers from the 19th century.

As world renowned Australian opal expert Len Cram says, “Opal is like gold, once the fever is in your blood you can never get it out”. Any opal cutter knows how right he is.